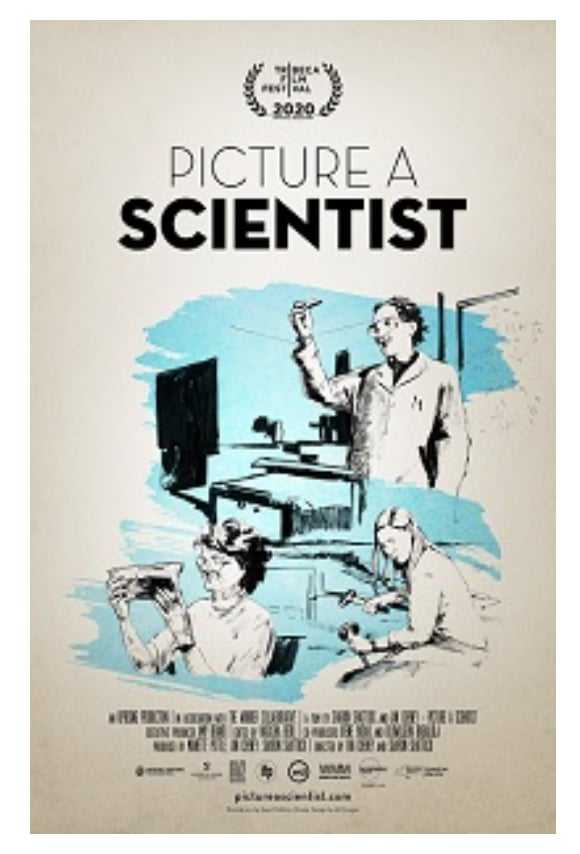

2020 Tribeca Film Festival film Picture a Scientist, which examines harassment of women in STEM and the cultural issues that drive attrition in scientific fields, was the focus of today's roundtable of scientists hosted by Ann Arbor's ProQuest and Scientific American's Editor-in-Chief Dr. Laura Helmuth. The main question? Why is women's attrition from STEM fields still such a resistant issue in the year 2021?

Panelists included Dr. Jennifer Doudna of UC Berkeley who was co-awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her revolutionary work creating CRISPR-Cas9--a genome engineering technology that allows researchers to edit DNA. Dr. Raychelle Burks, Associate Professor of Chemistry at American University, Dr. Jane Willenbring Associate Professor of Geological Sciences at Stanford, and Dr. Eva Pietri of the Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Social Intervention and Attitudes Lab joined Dr. Doudna to talk about the real issues underneath the problem. The event was attended by over 8500 people from over 150 countries, mostly academic institutions.

You can view a trailer of the movie Picture a Scientist here.

Dr. Jennifer Doudna of UC Berkeley, co-inventor of CRISPR gene editing technology.

The Leaky Pipeline Metaphor

The higher up you go the STEM pipeline, the more white, straight, and intellectually conservative people seem to be. Farther down the ladder, you find 50/50 women. What's the problem? The "leaky pipeline." Women have disproportionate attrition in scientific fields even starting in college, where classes can be evenly split female freshman year, and have almost no women by senior year. In STEM a lot of resources have been spent to get girls into the field by encouraging their passion for science and engineering and encouraging them through math. But according to panelists, sexual harassment creates leaks in the pipeline. Some of that work is being undone, as women don't drop out of STEM for lack of belief in their intellectual abilities but because they are actively sabotaged, overtly or covertly.

Pietri: "I have some criticism of the leaky pipeline metaphor. We don't want to place it on women as if they're leaking out of the pipeline. Rather there is a hostile environment where people won't hire women, create a hostile climate, so we don't place the blame on women. Research shows it's not a lack of interest or ability. Lots of women are coming in with a lot of excitement. Something about the climate is actively pushing them out."

You can't recruit women into a field and then set it up for failure, said another panelist. It's an expensive option to recruit girls into STEM, but it's easy because it doesn't require a deep fix into a systemic and cultural failure. It still puts the burden on individual institutions or individuals for dropping out. So what is the real issue here? And what are the possible solutions?

Dr. Raychelle Burks, Associate Professor of Chemistry at American University, whose research focuses on developing low-cost colorimetric sensors for detective chemicals of forensic interest.

Is Attrition the Right Word for Women Leaving STEM?

First off, panelists agreed that there is a problem of how we speak of women dropping out of STEM. It puts the onus on the individual for leaving, when many women don't want to leave the sciences at all. The consensus was that it's not simple attrition as much as it is a hostile environment that doesn't allow women the same opportunities for hiring in, advancement, or growth.

Toxic work environments were just the tip of the iceberg. There seems to be a growing awareness that these problems aren't always overt or conscious, and are driven by a culture that assumes on both sides of the gender divide that women should normalize difficult environments and challenges to normal advancement, especially the further up the ladder you go. And that usually doesn't look like unwanted sexual advances, but more commonly bias and micro-aggressions.

Doudna: "I feel quite fortunate that I have benefited from wonderful male and female mentors in my field, and have benefited from women who went ahead of me and create a friendly environment for women who want to be in STEM. I think a lot of the issues right now for women are largely ones of unintentional bias or not as overt as one might think but still have an impact on women's careers. Especially as they get further along and are vying for positions ... on boards and faculty positions ... that's where there is the greatest need for more diversity."

Burks: "Inequitable treatment is often overlooked because it's seen as the norm, and women often recalibrate their own expectations to normalize a situation.... I might be fine, but are we as equitable or inclusive as possible? We might be used to it, or we might benefit from it in some way. Am I the unreliable narrator in some way?... If we ask someone to demonstrate grit, is it scholastically challenging, or is it a toxic working environment? If we ask better questions, we can hopefully get to a point where we get better answers."

Pietri: "Recent studies showed gender bias in post-doc applications and showed Latinx and black women were less likely to be hired, so bias seems to persist.... If one is comfortable or able to [speak up], that person can reflect on that and hopefully change their behavior in the future. It's important that people speak out. From a policy standpoint this speaks to the importance of having organization so everybody has to watch the movie at the same time and have that conversation."

Dr. Jane Willenbring is Associate Professor of Geological Sciences at Stanford, and recipient of the Antarctica Service Medal from the US Armed Forces, as well as a National Science Foundation CAREER Award and Marguerite T. Williams award.

How Do You STEM The Tide of Women Leaving The Sciences?

This raised an important point: if organizations are dedicated to cultural change, one way to push for that is to gather employees for discussion that is intentional and synchronous. Other panelists pointed out that if someone is close to a change point where they're ready to accept a difficult reality such as the evidence for sexual harassment against women in STEM, they're less likely to argue against the evidence. If someone isn't near that point, change won't happen. But in an environment where organizations tackle harassment and bias consciously and spend time on the issue, it creates more opportunity for reflection and change, at least where it is welcome.

Willenbring: "When it's your own colleague, that's actually hard. It takes a lot of personal thought and gumption to support someone over someone you have known for a decade.... We should always at least try to be on the right side of history. I feel we have a pretty far way to go. I am often [approached] by younger folks who watched the film and I talk to them through Q&A. They always think their generation will be different. I think every generation thinks they will be different, and it doesn't work out that way. It's culture, and you have to make an active way to fix it. It doesn't just change by people retiring."

Many proposed solutions to these issues involved promoting systemic cultural change. Encouraging women to work with their own value in mind was an interesting specific suggestion in that direction. Women often feel if they can't accomplish for their own careers, they can dedicate themselves to their students, their children, their families. But do they understand that their own happiness matters, panelists asked? That they can work toward their own success for its own sake? The issue is on both sides, it seems. To stop normalizing micro aggressions that are the most common version of harassment in the workplace such as putdowns and exclusion from meetings, to the other side addressing what women have been taught to expect about what they can accomplish.

"Learn to separate yourself from the job," one panelist advised her younger self. "The job might be real trash, just poisonous people. But I would encourage my students or my younger self to keep the love of science separate from the job because we can mix those and forget the passion."

Dr. Eva Pietri's work has investigated how basic processes in social psychology influence a variety of domains that are pertinent to real-world issues, including promoting diversity in STEM fields. She is Assistant Professor in Psychology at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

Encouraging Diversity in STEM

Doudna: "In my case, I had my share of detractors or people who have not been encouraging along the way but I guess I've tried to seek out people who would help me or be supportive. We all need that at times in our careers.... Ensuring our students feel the responsibility they will have when they step into roles as mentors or colleagues to support them, especially female, but anybody in STEM. The real key to innovation is to have a diverse perspective, and how better to get that than to have people in the room who have not traditionally been in our community?"

Pietri: "I'm lucky that there are more women represented in social psychology, though we see less of that the higher you go as you see in any STEM field.... One thing I've noticed that inspired some of my research questions: it's not just seeing a lack of women. I'm Puerto Rican. I never had an instructor with my same identity. I was reflecting on the first time I saw a Latinx researcher.... I had never thought about it up to that point, but it was exciting to see someone who looked like me."

As the sciences become more conscious of the depth of the problem beyond overt sexual harassment, we hope to see more of these types of deeper questions that get at the underlying issues of diverse perspectives, expectation, culture, and norms. If you would like to view the full movie Picture a Scientist, it is available through ProQuest via your academic institution or host a screening.